|

Website under construction

Proposal Draft

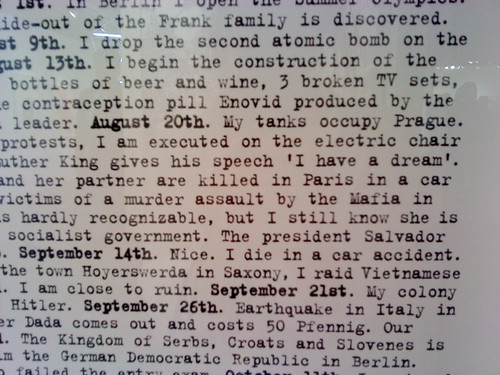

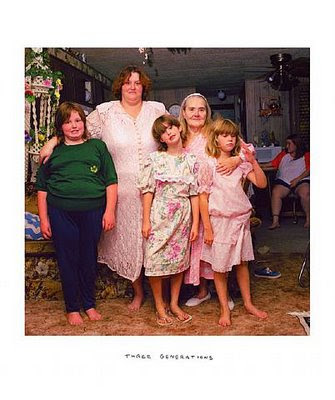

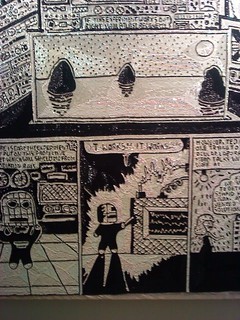

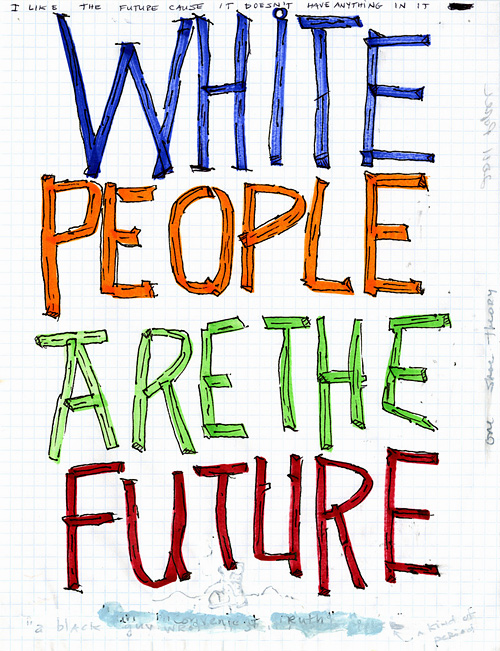

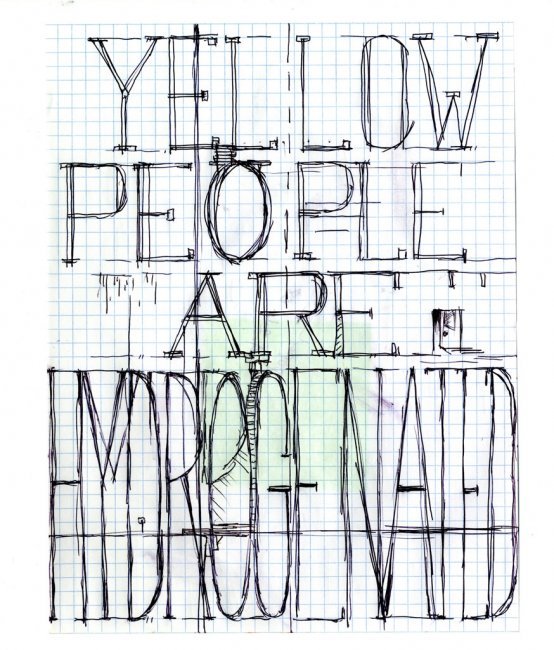

The jpgs here are examples of the artists work.

This is an idea in progress.

None of the artists have been contacted.

The first iteration of Colored Stories originally appeared in 1995 on the online site Scope Art Gallery with the subtitle was Depictions of Race in Narrative Art. Since then, the discussion of race in the US has changed with the influx of new immigrants especially Latinos and North and South Asians. This proposal is for a show that broadens in scope to include all types of discrimination including classism, ageism, and discrimination against LGBT people. The time frame is 1940s to present. Other issues to be addressed: Why is the narrative text-image format so often used for race/discrimination issues. Why does text so often become crucial when trying to address the very specific subject of discrimination? There is an urgency in the message. Does that make the usual artistic option for multiple interpretations distracting? Did it become codified with Jacob Lawrence and later Faith Ringgold as the best way of communicating about discrimination? Is that evidenced in David Wojanarovitch's This Boy. Fighting discrimination may be a better title.

Afro Cobra

Carla Gannis

Carrie Mae Weems

Chris Verene

Christina Marsh

Ode: Study of White, 2006 acrylic on panel Daniel Gonzalez

sequins on canvas

Guerilla Girls

Jacob Lawrence

Jean Michele Basquiat

Jeremiah Johnson

Kara Walker

Kenneth Apetaker

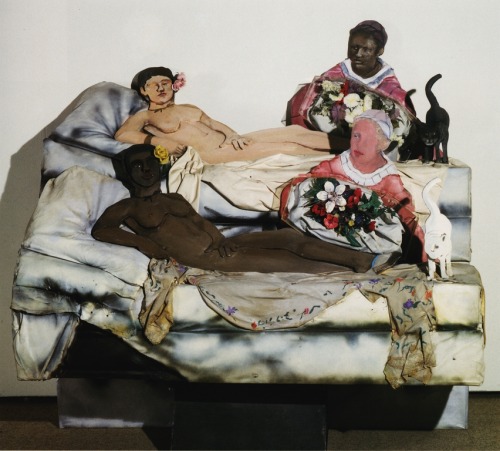

Kerry James Marshall

Larry Rivers

Linda Griggs

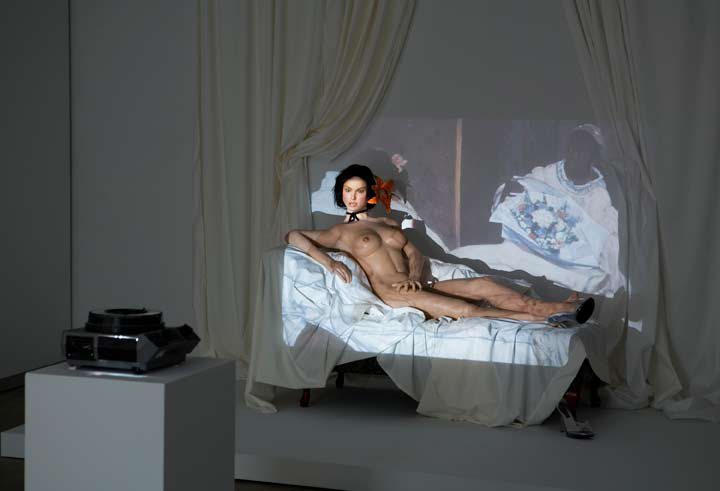

Lynn Hershman Leeson

“a custom sex doll created to resemble Manet’s Olympia” from the Found Object Series.

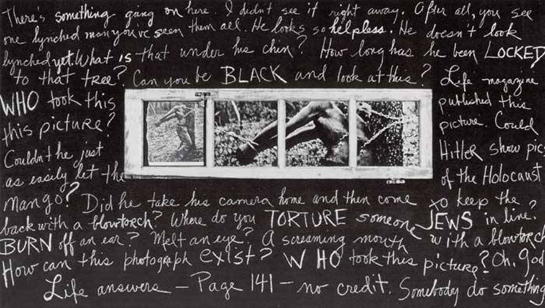

Pat Ward Williams

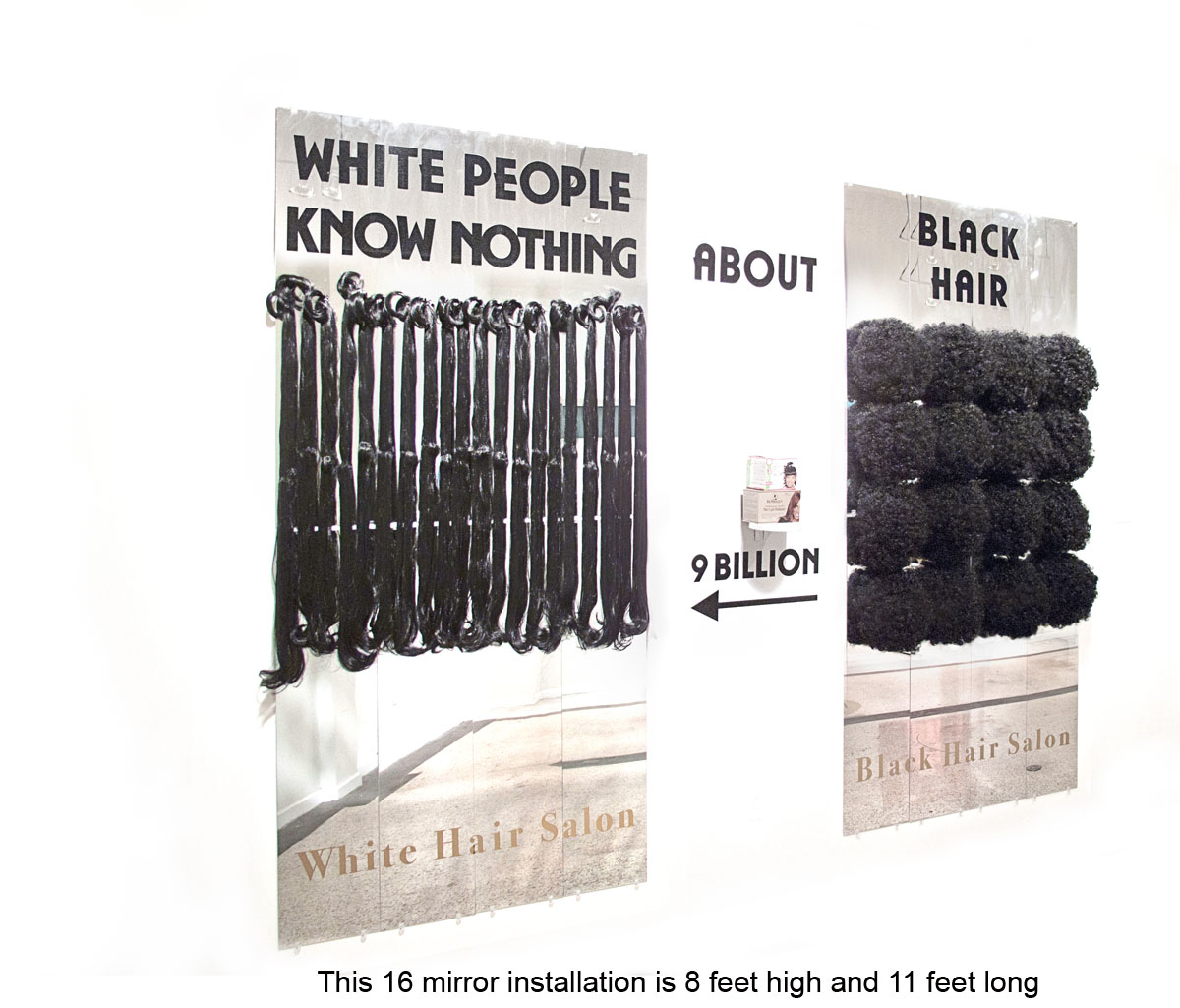

Rashid Johnson

Sue Coe

Theaster Gates

Virginie Sommet

William Pope.L

Other concepts to be considered and addressed:

Seventy years ago, half of all Americans read comic books, and much of what they saw were stereotypical images of Asian kamikazes, gurus, temptresses, and lotus flowers. How did Asian Americans read these images? How do they see them now? Jeff Yang, blogger and writer for the Wall Street Journal, curated two new exhibits at the Museum of Chinese in America that explore these questions. Through "Marvels and Monsters: Unmasking Asian Images in U.S. Comics, 1942-1986," and "Alt.Comics: Asian American Artists Reinvent the Comic," Yang wanted to address and expose the stereotypes, and show the ways in which modern comics are combating them. ... Some African American artists find the narrative art format has become such an accepted standard as to be oppressive in itself to African-American artists that choose not to make didactic narrative art. "Melvin Edwards and his current exhibition at MoMA’s PS1: “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980.” The article’s author, Carol Kino, writes:

Sequential Art: Any series of images that are supposed to be viewed in a specific order. http://myweb.stedwards.edu/lauraah/syllabi/ARTS4399_SequentialArt_F08.pdf Course Description: This course will take a broad look into Sequential Art: content, concept, subject, narrative, storytelling, and much more. We will investigate many different forms, and will study the conventions associated with this broad field of Narrative Art. This is a cross-disciplinary course where majors from all areas can explore the form of Sequential Art in a variety of mediums. We will look at and research diverse styles and forms ranging from the silent narrative, the comic strip, and the flipbook, to serial photography. We will study works of art from the ancient to the contemporary, from the high to the low, from paintings to video to alternative comics. We will not focus on the mainstream world of comics, but rather more obscure or alternative publications. We will not focus on the specifics of rendering, techniques, materials, or tools. Instead each of you will be encouraged to experiment with different styles and media, inventing and playing within the constructs of the narrative sequence.

|

|||||||